Fort Bunker Hill Park

Washington, DC | 2015

Cultural Landscape Inventory

Project Team: Randall Mason, Molly Lester, Joseph Mester

History

Fort Bunker Hill was one of the 68 forts built as a defensive ring around Washington at the start of the Civil War. It was among the first of the fort sites to be surveyed and acquired, with construction underway by the fall of 1861. It was constructed by General Joseph Hooker’s Brigade (including the First and Eleventh Massachusetts, Second New Hampshire, and Twenty-Sixth Pennsylvania volunteer regiments), which was part of the restructuring of General Irvin McDowell’s army into General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. The hilltop earthwork, erected on the acquisitioned property of Jehiel Brooks, received its official designation as Fort Bunker Hill on September 30, 1861, by order of McClellan. It was part of the northern arc of the Defenses of Washington, which were selected and constructed in anticipation of a possible attack from the north, as Washington, DC had faced during the War of 1812.

As was the case with several of the fortifications, Fort Bunker Hill continued to be modified and altered over the course of the war, as the army’s engineers addressed structural and visibility issues with the fort’s design. By December 1862, Chief Engineer J. G. Barnard called for two additional batteries to be constructed to support Fort Bunker Hill. One of the batteries occupied an advanced position on the northeastern slope of the hill with Fort Bunker Hill, while the other flanked Fort Bunker Hill on the low hill southeast of the fort. These batteries with covered ways were likely completed in early 1863, but they still deemed weak by late June 1863, so a third battery was constructed on a rise northwest of Fort Bunker Hill. The third battery was likely complete by late 1863.

On the southwestern slope of Fort Bunker Hill, numerous wood-framed buildings were erected to house and provide services for the garrison of Fort Bunker Hill and its supporting batteries. Because space within the earthwork was limited, the support structures were erected outside of the fort’s parapet walls. By war’s end, there were 32 framed structures on the Queen/Brooks property (outside the confines of the earthworks). They included sixteen quarters for commissions and non-commissioned officers, three barracks for enlisted artillerymen, two guardhouses, five stables, a horse shed, a blacksmith shop, a post office, and a prison.

Despite—or perhaps because of—these alterations, Fort Bunker Hill and the other defenses were never subject to a Confederate attack. Their usefulness as a deterrent was clear, however, as General Early attested after the war. Fort Bunker Hill, together with the other forts in the northern arc, was therefore critical as a buttress in the city’s defense.

As the war came to an end and the structures were sold at auction, the Queen/Brooks family retook possession of the fort and its surrounding land. Although they resumed farming the larger estate after the war, the hilltop fort site was difficult to plow and thus remained intact and largely untouched. Bellair, the Brooks mansion, remained standing southwest of the earthworks, and by 1884, the former Bladensburg Road west of the fort was newly renamed as Bunker Hill Road.

Even more significantly for the fort’s larger landscape and context, the Metropolitan Branch of the Baltimore and Ohio (B&O) Railroad was introduced in 1873, running north-south to the west of the earthworks, and the Brookland subdivision was created around Fort Bunker Hill in 1887 as one of Washington, DC’s first streetcar suburbs. Soon after, the area around the fort site was platted with a street grid and narrow lots, but the fort itself remained largely intact within the perimeter streets of Fort Street to the south, 13th Street NE to the west, Omaha Street to the north, and 14th Street NE to the east. Within just a few years of Brookland’s creation as a subdivision, newspaper accounts indicate that the Brookland Citizens’ Association had formed, and that the association supported the creation of a public park on the site of Fort Bunker Hill.

In 1902, the publication of the McMillan Plan bolstered the Citizens’ Association’s cause and spurred efforts to preserve Fort Bunker Hill as part of a circle of green spaces around the city. This ring of parks would be established on the former sites of the Civil War Defenses of Washington, as part of the City Beautiful movement’s re-envisioning of the District of Columbia. Fort Bunker Hill was, by this time, surrounded by suburban development, and the site itself featured a limited number of houses around its periphery.

The District’s efforts to acquire the land stalled until the late 1920s, when the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) was authorized to purchase land related to the Civil War Defenses of Washington. A year later, on April 30, 1926, Congress replaced NCPC with the larger and more empowered National Capital Park and Planning Commission (NCPPC), and in 1927, the NCPPC purchased the site of Fort Bunker Hill.

The creation of the park at Fort Bunker Hill corresponded with the formation of the Civilian Conservation Corps during the Great Depression. By the end of 1935, CCC members from Camp NP-8-VA began work at Fort Bunker Hill, where the CCC’s projects included not only the planting of trees and the construction of walkways, but also the development of the site as a recreational area—most significantly with the construction of an amphitheater on the site’s eastern slope. It included a stage, circumscribed by a wall 65 feet long and three feet high, with fixed log seats for 250 people set into the hillside. An additional 150 audience members could be accommodated on the ground or in portable chairs.

Analysis + Evaluation

Today, Fort Bunker Hill is situated in the midst of a largely residential area of northeast Washington, DC, near the Franciscan Monastery of the Holy Land in America (northeast of the site) and Catholic University of America (west of the site). Its Civil War earthworks are largely demolished or deteriorated, although some remnants are visible. The landscape retains most of the vegetation pattern and features from its 20th century conversion to a park, including the amphitheater on its eastern slope, its circulation pattern around the cleared hilltop, its overgrown hillsides, and the grassy periphery along the encompassing streets.

Fort Bunker Hill exhibits the following landscape characteristics: topography, spatial organization, land use, buildings and structures, circulation, vegetation, views and vistas, and small-scale features.

Topography: The site for Fort Bunker Hill was selected for its topography. Its position at 230 feet above sea level provided an elevated vantage of the surrounding landscape, including several strategic sites that Fort Bunker Hill was designed to protect. The topography remains the same as it was throughout the historic period, and retains a high degree of integrity.

Spatial Organization: The spatial organization of Fort Bunker Hill dates to the later part of the historic period, when the site was converted to a park and the CCC implemented various recreation improvement and beautification projects on the site. There have been minor additions to the landscape in the form of wayfinding and interpretive signs since the later period of significance, but the site retains its historic spatial organization and has a high degree of integrity.

Land Use: The Civil War-era military land use aspect of the Fort Bunker Hill cultural landscape ended when the United States government sold the property in 1865. However, the land use at Fort Bunker Hill has not changed since the 20th century period of significance. The site remains a public park, and is used for recreation, education, and interpretation. As it has since the CCC era of involvement at the site, the park serves a public function and is open for general recreational use. Land use at Fort Bunker Hill retains integrity.

Buildings and Structures: The site has some integrity of buildings and structures from each of its two periods of significance. From its Civil War-era period of significance, portions of Fort Bunker Hill’s earthworks remain intact. This includes remnants of the sally port, parapets, rifle pits, outer ditch, and likely evidence of the magazine. The other auxiliary buildings and structures that stood on the site during its 19th century period of significance are no longer present. From the site’s 20th century period of significance, the amphitheater and stage installed by the Civilian Conservation Corps remain partially intact. The site retains integrity of buildings and structures.

Circulation: Fort Bunker Hill’s Civil War era circulation pattern, including its military access road from the former Bladensburg Road (later Bunker Hill Road, now Michigan Avenue) southwest of the earthworks, does not exist on the site today. Some or all of the current social paths, however, likely date to the CCC’s interventions at the site during the later period of significance. These social trails include a path from the lowest area of the site, on the eastern edge along 14th Street NE, through the historic amphitheater and up the hill to the earthworks at the highest point on the site, on the western edge along 13th Street NE. The site therefore retains some integrity of circulation.

Vegetation: There was limited vegetation at Fort Bunker Hill during the Civil War, in keeping with the site’s strategic design and use. The current vegetation pattern is not, therefore, consistent with the 19th century period of significance, but the mature trees and cleared, grassy areas (around the edge of the site and on the hilltop) do likely date to—or predate—the CCC-era period of significance and their projects on the site. Fort Bunker Hill’s vegetation retains integrity from its 20th century period of significance.

Views and Vistas: The views and vistas from Fort Bunker Hill during the Civil War extended to the countryside surrounding the fort—in particular, towards the north and east. These vistas remained intact for several years after the war, but the redevelopment of the site and the surrounding area in the late 19th century—and in particular, the construction of the Brookland subdivision around the site—affected the views from the landscape at Fort Bunker Hill. In addition, during the later periods of significance, vegetation growth within the site has also affected the historic views from the 19th century period of significance. The present day views and vistas therefore retain integrity, consistent only with the 20th century period of significance.

Small-Scale Features: Fort Bunker Hill’s small-scale features have little to no integrity. The site has no surviving features from its 19th century period of significance. Most of the extant features, including signage (regulatory and wayfinding), picnic tables, and a commemorative boulder and plaque, were installed at the site after the 20th century period of significance and are non-contributing. Other non-contributing features include the two concrete drinking fountains, located adjacent to the amphitheater and along the social trail at the center of the site near the remnants of the outer ditch. These fountains are not consistent with the water fountains installed by the CCC, which were constructed using hollow logs. The contributing status cannot be determined for two features at the site. The two tall light standards are located in the amphitheater area and provided stage lighting to performances; it is not known when they were added to the site, but the documentary evidence from the CCC’s work on the site makes no reference to them. In addition, a small concrete pier is located near the amphitheater stage, but further research is necessary to clarify its function and time of construction. The small-scale features of Fort Bunker Hill’s cultural landscape therefore do not retain integrity.

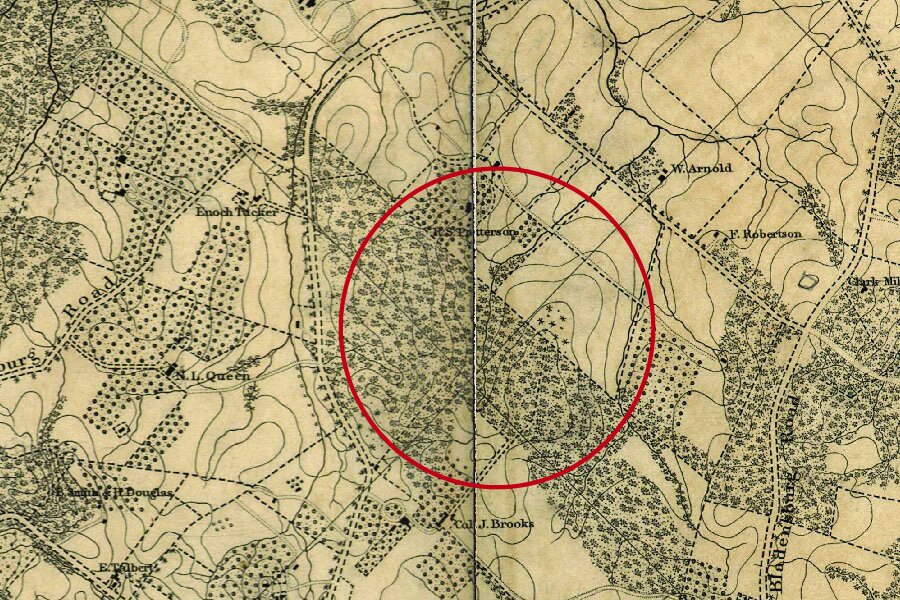

1861: Boschke map of the District of Columbia, with future hilltop site of Fort Bunker Hill highlighted. (Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division)

Modified 1865 map of the Defenses of Washington, distinguished by their current ownership and management status. (National Park Service)

Comparison of the site of Fort Bunker Hill, as depicted on the 1861 Boschke map (left) and the 1861 Lines of Defense map (right), developed by Major General John G. Barnard. Barnard’s map of the fortifications around Washington used Boschke’s survey as a base map, superimposing the location of the hastily-built forts on the existing map. (Boschke map, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division; Lines of Defense map, Historic Map Works Rare Historic Maps Collection)

Early map of Fort Bunker Hill environs (date unknown). (National Archives, as printed in Cooling and Owen 2010)

Engineer drawings of Fort Bunker Hill’s magazine (top), sections and elevations (center left, center right, bottom), and plan (center). (National Archives, as printed in Cooling and Owen 2010)

By 1907, the site was fully surrounded by the Brookland subdivision, confined to a city block bound by 14th (formerly Argyle) Street NE, Perry (formerly Omaha) Street, 13th (formerly Burns) Street NE, and Otis (formerly Fort) Street. (Baist 1907, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division)

View looking west at the Fort Bunker Hill amphitheater, constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps, in a c. 1960 photograph. (National Park Service, as printed in Einberger 2014)

Fort Bunker Hill’s historic circulation pattern during the early period of significance, as represented in the 1863 Topographical Map of the Defenses North of Washington. During the Civil War, the site had a limited number of access roads from Military Road (to the south), but few social trails and no connections to the land north or east of the fort. In contrast, the site today (as seen in an aerial photograph) has several social trails, including the primary social trail along the central east-west axis of the site. (Hodasevich 1863, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division; United States Geological Survey 2006, via Google Earth)

Fort Bunker Hill’s extant social trails are dirt paths. The primary social trail (left, looking west) has remnants of the CCC-era steps. In some areas, the paths are overgrown with vegetation. (M. Lester 2015)

Fort Bunker Hill’s vegetation pattern has changed significantly over time, from its clearcut condition during the Civil War (top); to the 1880s (center), when vegetation overtook the hilltop and the earthworks; to the current condition (bottom), which is densely wooded throughout the site. The earthworks are located in the southwest corner of the city block that contains Fort Bunker Hill Park. (Hodasevich 1863, Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division; Lydecker and Greene 1884, NOAA Historical Map and Chart Collection; United States Geological Survey 2008, via Google Earth)

Fort Bunker Hill’s current vegetation is generally densely wooded and overgrown at the perimeter (top, view looking north), with limited exceptions that include cleared areas at the corners of the block (center, view looking west) and an area along the eastern side of the site (bottom, view looking west) that has minimal ground cover. (M. Lester 2015)

Within the Fort Bunker Hill site, the vegetation pattern generally consists of a thick growth of mature trees and low brush (top, view looking north; center, view looking north). At the crest of the hill in the southwest corner of the site (bottom, view looking northwest), a cleared area has minimal ground cover and few trees. (M. Lester 2015)

Fort Bunker Hill’s earthworks over time, from the planned layout at the start of the Civil War (left) to the gradual deterioration in the late nineteenth century (center) to their current condition (right), as seen in a recent aerial photograph. (National Archives, as printed in Cooling and Owen 2010; Lydecker and Greene 1884, NOAA Historical Map and Chart Collection; DigitalGlobe 2015, via Google Earth)

The historic earthworks are still somewhat legible in the site’s topography, although their condition has deteriorated and they are obscured by vegetation. Parapet remnants are visible in the top (view looking east) and center (view looking west) photographs, while the bottom photograph (view looking north) depicts the traverse within the parapets. (M. Lester 2015)

Views of the CCC-era amphitheater, including the concrete stage (top, view looking south) and the deteriorated hillside seating (bottom, view looking southwest), which retains traces of the rustic log seating that the Civilian Conservation Corps constructed between 1935 and 1937. (M. Lester 2015)

The site’s original views toward the surrounding land north and east of the fort are obstructed today by vegetation and development around the hill. Top: view looking south; Bottom: view looking north. (M. Lester 2015)

Extant small-scale features on the site include the picnic tables and signage in the southeast corner of the park (left, view looking west); concrete water fountains (center, view looking east), which likely postdate the later period of significance; and two lightstands around the amphitheater (right, view looking north) that may date to the CCC-era period of significance. (M. Lester 2015)