Lincoln Memorial

Washington, DC | 2021 - 2022

Cultural Landscape Inventory

Project Team: Randall Mason, Molly Lester, Jacob Torkelson, Christine Chung

History

The Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape (Reservation 332) is a component landscape of West Potomac Park. The study area for this Cultural Landscape Inventory encompassed 83 acres and included the Lincoln Memorial structure and circle, Reflecting Pool, the John Ericsson Monument, the Watergate Steps area, and the Belvedere at Peters Point.

—

The Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape was reclaimed from the Potomac mudflats in the late 19th century. It was formalized as part of West Potomac Park in 1897, and was a focal point of the 1901/1902 McMillan Plan, which called for the creation of a national monument at the west end of the National Mall to honor President Abraham Lincoln and commemorate the reunification of the country after the Civil War.

Congress established the Commission of Fine Arts in 1910 and the Lincoln Memorial Commission in 1911; both agencies were responsible for commissioning the structure and statue that would be the centerpieces of the Lincoln Memorial itself. Architect Henry Bacon was selected to complete the design for the structure, and Daniel Chester French received the commission for the statue. The groundbreaking for the structure was on February 12, 1914, and work was substantially complete by the dedication ceremony on May 30, 1922.

The landscape around the memorial structure, including the prominent Reflecting Pool feature, was designed by Henry Bacon, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., and others. The landscape was improved throughout the 1910s and 1920s, although the areas north and south of the Reflecting Pool were commandeered for temporary war buildings starting in 1918.

In 1939, Marian Anderson held a concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial for 75,000 people. Organized by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other organizations as a rebuke to segregationist actions by the Daughters of the American Revolution, the event established the Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape as a site for civic protest and gatherings associated with the Civil Rights Movement.

In August 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. extended this protest use, issuing his famous “I Have a Dream” speech from the steps of the memorial as part of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The site’s historic use as a site of recreation, commemoration, and protest has continued to the present day.

Significance

In addition to its designation on the National Register of Historic Places, the Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape was previously documented in 1999 with a Cultural Landscape Report Part I. The 1999 CLR identified two periods of significance for the cultural landscape: 1791-1914, which spans the early development of Washington, D.C., the creation of parkland from the tidal flats of the Potomac River, and the recommendations and early implementation of the McMillan Plan; and 1914-1933, encompassing the design development, construction, and completion of the memorial, surrounding grounds, and significant associated features. The CLR considered the second period (1914-1933) to be of primary significance, since it had the most pronounced impact on the physical development and spatial organization of the cultural landscape; the period 1791-1914 was therefore a secondary period of significance for the cultural landscape. The CLR documented three additional periods (1933-1945, 1945-1970, and 1970-1996) based on their implications for NPS management and physical development, but did not characterize these later periods as significant.

This 2022 CLI concurs with the findings of the 1999 CLR with respect to the first two periods of significance (1791-1914, 1914-1933). It recommends an additional period of significance that begins in 1939 and extends to the present, acknowledging the nationally significant commemorative and protest uses that the cultural landscape has represented historically and continues to represent today.

The first period of significance (1791-1914) begins with Pierre L’Enfant’s 1791 plan for the city of Washington, which established an American model for urban design based on Baroque city plans, and culminates with the 1914 groundbreaking ceremony for the Lincoln Memorial. Within that 123-year span, the cultural landscape was created from the Potomac River flats and became a focal point of the 1901 McMillan Plan for improvements to the park system in Washington, D.C. The period of significance also includes the creation of the Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) in 1910, a nationally significant body responsible for advising the government on the development of Washington, D.C.’s public buildings and landscapes. The CFA played a key role in shaping the design of the cultural landscape, influencing the refinements to Henry Bacon’s 1911 design for the Lincoln Memorial structure and grounds.

The second period of significance (1914-1933) encompasses the decades-long design development, construction, and initial improvement of the Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape. The cultural landscape was constructed in phases, beginning in 1914 with the memorial structure and continuing for nearly 20 years, progressing with the construction of the allées, east circle plantings, Reflecting and Rainbow Pools, John Ericsson Monument, and finally in 1932-1933, the Watergate Steps area and west circle plantings.

The third period of significance (1939-present) begins with Marian Anderson’s Easter Sunday concert at the Lincoln Memorial. When the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) barred Anderson from performing at the organization’s Constitution Hall because she was Black, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) arranged for Anderson to sing at the Lincoln Memorial instead. With the support of First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, Anderson performed for a crowd of 75,000, including members of the Supreme Court, Congress, and the President’s cabinet, as well as a national radio audience. The event solidified the Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape’s association with the Civil Rights Movement—and with protest/commemorative movements in general—as the building and landscape played host to a nationally significant event for racial justice. This pattern and use of the cultural landscape continued through subsequent decades, most notably with the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, an event that built on decades of civil rights activism and culminated at the Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape on August 28, 1963. The march brought together six of the leading civil rights organizers of the time: A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, organizers of the march; Roy Wilkins of the NAACP; John Lewis of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); and Martin Luther King, Jr. Over 300,000 people gathered for a rally at the Lincoln Memorial and around the Reflecting Pool, where they heard Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famous “I have a dream” speech. The rally confirmed the symbolism at the root of the Lincoln Memorial’s creation and design.

This period of significance is continuous from 1939 to the present, recognizing that the symbolic use of the cultural landscape as a place of protest and commemoration remains active today.

Analysis + Evaluation

The Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape consists of the following contributing landscape characteristics: spatial organization, land use, topography, vegetation, circulation, buildings and structures, views and vistas, constructed water features, and small-scale features.

Spatial Organization: The spatial organization of the Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape is consistent with its composition during the site preparation and construction periods of significance (1791-1914, 1914-1933), despite changes to its design made during the protest period of significance (1939 - present). The addition of disruptive circulation features after the construction period of significance has hindered the historic design, feeling, and association of the landscape in the northwestern portion of the cultural landscape. These features severed the Belvedere from Constitution Avenue and carved up open space into smaller parcels. Despite these alterations, the greater design principles delineated in the plans of L’Enfant, the McMillan Commission, and the 20th century designers (including Bacon, Olmsted, and others) are clearly legible within the majority of the cultural landscape. As a result, it retains integrity with respect to spatial organization.

Land Use: The Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape remains significant with respect to land use, as it continues to accommodate and encourage commemorative, recreational, and protest uses. Localized changes to land use, e.g. the addition of service uses, do not detract from the landscape’s historic designed use.

Topography: Despite changes to specific areas of topography due to circulation changes in the second half of the 20th century, the cultural landscape retains its general shape and landform established during the site preparation and construction periods. The addition of highway berms in the northwest portion of the cultural landscape has had a detrimental effect, but other minor changes, including the addition of retaining walls and ramps at the west end of the Reflecting Pool, do not detract from the integrity of the landscape. Overall, the cultural landscape retains the conception of the centrally located and elevated Lincoln Memorial structure, the terraced Watergate Steps, and the sunken Reflecting Pool area. Accordingly, the cultural landscape retains its integrity with respect to topography.

Vegetation Summary: Minor alterations have affected individual plantings within the cultural landscape since the end of the construction period of significance (1914-1933). However, these changes do not detract from the overall integrity or legibility of the cultural landscape’s vegetation features. The elm allées established in the 1910s and 1920s, as well as the evergreen planting palette established in the 1920s and 1930s, are still legible today, retaining their overall composition through historic and in-kind plantings. All sections of the cultural landscape retain turf panels consistent with their historic designs. Non-historic plantings in all sections largely adhere to the historic species list, owing to careful rehabilitations in recent years. Although some newer plantings represent non-historic species—including understory and mid-story species in particular areas—they nevertheless adhere to the historic designs of the Lincoln Memorial. As such, the cultural landscape retains integrity with respect to vegetation.

Circulation: Overall, the extant circulation features within the Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape are consistent with conditions at the end of the construction period of significance (1914-1933). Significant extant contributing features throughout the landscape include the radial roads, Approachway, Watergate Steps, and Reflecting Pool allée walkways. Non-contributing circulation features include highway entrance and exit ramps, east-west walkways immediately adjacent to the Reflecting Pool, and accessible ramps throughout the cultural landscape. Significant non-contributing circulation features such as Independence Avenue SW and the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge ramps do detract from the overall legibility of the historic circulation plan, but their impact does not affect all aspects of the landscape’s circulation. Recent non-contributing changes to paving and direction of use, and the introduction of new accessible circulation features, do not detract from historic conditions. Despite changes, the Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape therefore retains integrity with respect to circulation.

Buildings and Structures: The cultural landscape features many buildings and structures dating to the period of significance. This includes the Lincoln Memorial structure and its raised terrace, the John Ericsson Monument, the Constitution Avenue Belvedere, and the parkway overpasses that have served historically as the anchors within the cultural landscape. Most of these structures date to the construction period of significance (1914-1933), and several have their roots even earlier in the site preparation period of significance (1791-1914). Buildings and structures added after the first two periods of significance include information kiosks, security barriers, and food service buildings. These features are non-contributing but are in keeping with the conditions that existed during first two periods of significance. Buildings and structures used by activists during the protest period of significance include the Lincoln Memorial and its raised terrace—both of which are retained and unchanged from the periods of significance. As a result, the cultural landscape retains integrity with respect to buildings and structures.

Views and Vistas: The Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape retains the views and vistas consistent with its periods of significance, including the external views toward prominent District landmarks and directed internal views based on various historic landscape plans. Changes to the viewsheds based on the construction of new bridges and circulation features have altered the historic views in these areas (particularly in the northwest corner of the cultural landscape), but do not detract from the overall integrity of the cultural landscape’s views and vistas. The most harmful impact to the views and vistas is represented by the oversized historic plantings, which infringe on the intended views from the north, south, and west sides of the Lincoln Memorial structure and detract from the vista of the memorial structure from the east. Despite these impacts, the legibility of the cultural landscape’s historic views and vistas remains largely intact, and it retains integrity with respect to views and vistas.

Constructed Water Features: The Reflecting Pool, the only constructed water feature in the cultural landscape, retains its historic design and approximate dimensions. It retains all seven aspects of integrity and as a result, the cultural landscape retains its integrity with respect to constructed water features.

Small-Scale Features: The cultural landscape retains many of its contributing small-scale features and those managed as cultural resources, including its stone Approachway benches, lampposts, and memorial tree plaques. Most of the non-contributing small-scale features—including some benches, lighting, drinking fountains, waste receptacles, and signage— postdate the original design of the landscape, and were added to adapt the landscape according to evolving visitation needs. Many of these features have been replaced regularly throughout the cultural landscape’s history. Because this memorial landscape is so highly visible, design interventions for new small-scale features have been sensitive and deferential to the historic design. Accordingly, small-scale features installed after the construction period of significance (1914-1933) do not detract from the legibility of the landscape’s overall character and design. It therefore retains integrity with respect to small-scale features.

1882 Map of Washington and Georgetown Harbors showing visible accumulation of sediment below the Long Bridge. (Library of Congress)

The 1901/1902 McMillan Plan was the basis for the eventual design of the Lincoln Memorial and its associated grounds, establishing the placement of the memorial structure along the Potomac River shoreline and delineating distinct areas within the landscape. (Excerpt from Moore 1902)

The McMillan Plan proposed a memorial temple structure that would be elevated on a rond point, at the west end of the proposed site. (Moore 1902: Plate 49)

Henry Bacon’s early design for the Lincoln Memorial included a colonnaded, open-air structure built around a memorial statue and elevated above a large water feature. (National Archives)

One of John Russell Pope’s designs for the memorial presented a large colonnaded exedra, with memorial statues in front. This design was the closest in concept to Henry Bacon’s design for the structure and landscape. (National Archives)

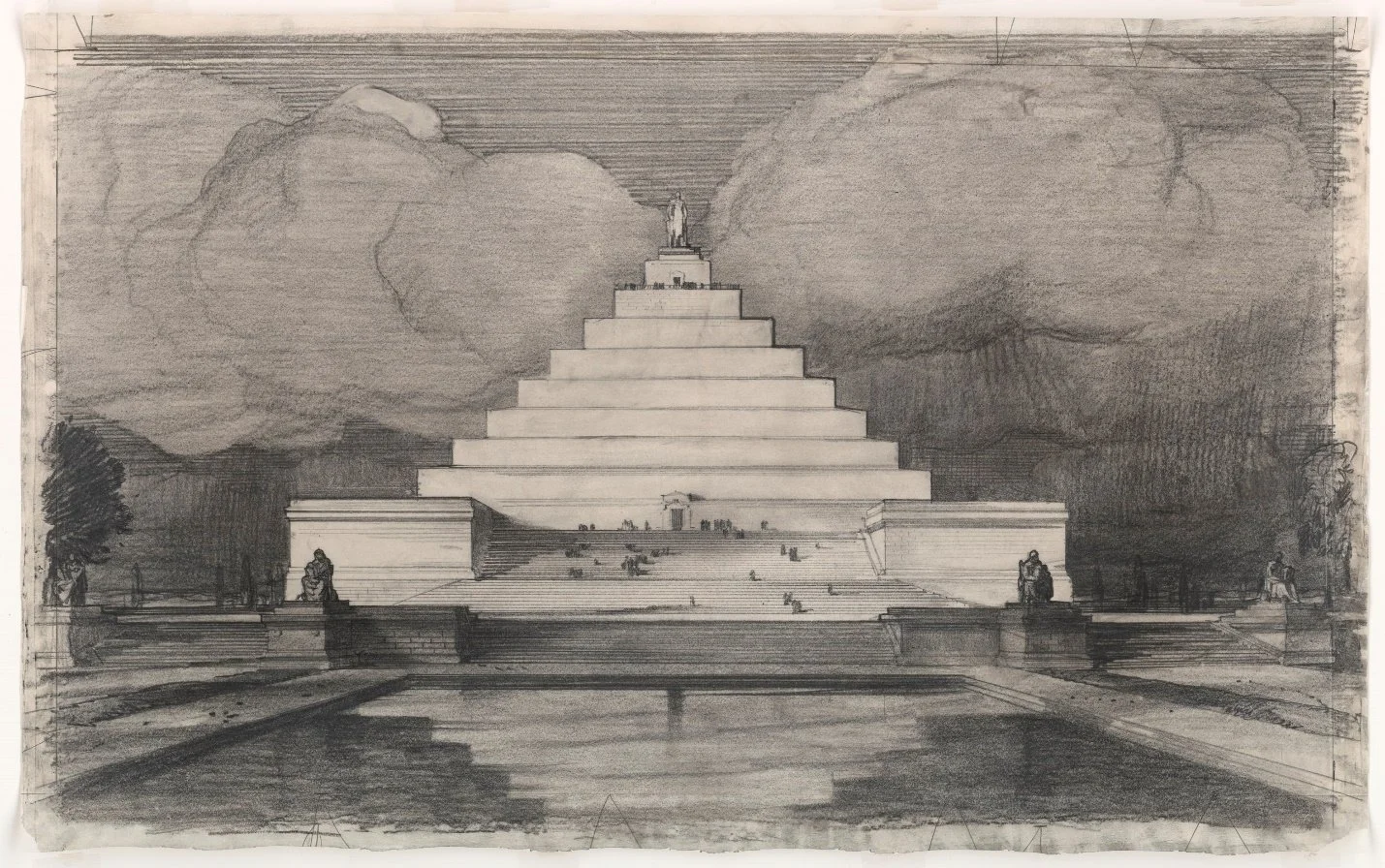

John Russell Pope’s third conceptual design proposed a ziggurat structure, foregrounded by a water feature. (National Archives)

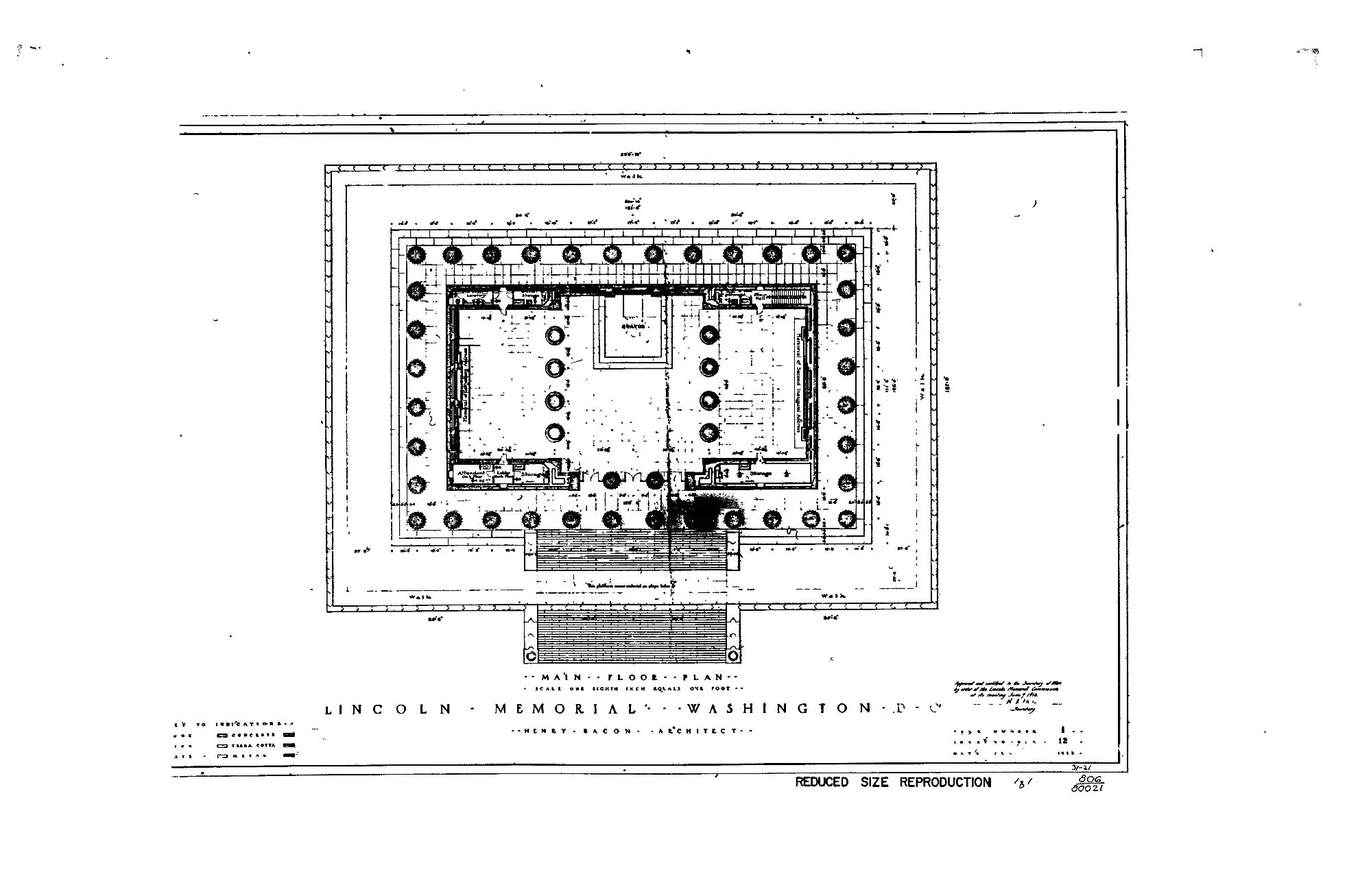

Floor plan for the Lincoln Memorial structure as of 1915. (Bacon 1915)

East elevation drawing for the Lincoln Memorial structure, as of 1915. (Bacon 1915)

Laying of the cornerstone on February 12, 1915. (Harris & Ewing Collection, Library of Congress)

Lincoln Memorial structure under construction, c. 1916. (Harris & Ewing Collection, Library of Congress)

The structure and landscape as of 1921. Note the temporary war buildings in the northeast section of the contextual landscape, north of the Reflecting Pool allée. (National Archives)

Aerial view of the Lincoln Memorial cultural landscape as of the dedication ceremony on May 30, 1922. (Library of Congress)

1934 view of the site. The storage tunnel is in place northeast of the Watergate Steps. (War Department, Army Air Forces 1934)

On April 9, 1939, Marian Anderson performed a concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial after being barred from performing in the DAR’s Constitution Hall. She drew a crowd estimated at 75,000 people. (Library of Congress)

As Marian Anderson’s concert had done, the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom took advantage of the Lincoln Memorial’s structure and site design to convene a rally for an estimated 300,000 people. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his famous “I Have A Dream” speech at this event. (Library of Congress)

In 1968, the Resurrection City camp was located on the lawns south of the Reflecting Pool and its southern allée. Aerial view from Lincoln Memorial Circle, looking west toward the Washington Monument. (O’Halloran 1968)

View to east of the Washington Monument and U.S. Capitol showing the axiality of the Reflecting Pool area, expressed by the east-west footprint of the pool and the primary allées that line the pool. (Torkelson 2021)

View to east showing the axial spatial organization of the Reflecting Pool area via the primary allées that line the pool. (Torkelson 2021)

An example of the topographic edge conditions of the cultural landscape (seen here at the Belvedere), featuring a slight slope terminated by seawalls or other retaining walls. View to the north along Parkway Drive SW of the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge overpass (background). (Torkelson 2021)

View to the northeast of the terraced topography of the Reflecting Pool’s west end. (Torkelson 2021)

View to the southeast of the Watergate Steps area’s steep topography, sloping down to the Potomac River. Note the Watergate Steps and the surrounding steeply sloped planting beds and retaining walls. (Lester 2021)

View to the southwest of the plantings at the front of the Lincoln Memorial. These are mostly groomed boxwoods and yews. (Lester 2021)

View to the southwest of the plantings around the Ericsson Memorial. The planting beds around the memorial presently contain Mountain Witch Hazel (Fothergilla major) but would have featured a variety of yews and mugo pine. Beyond the memorial, Ohio Drive SW contains riparian plantings of elm, cherry, and weeping willow. (Torkelson 2021)

View to south of the elm allées along 23rd Street SW. Note the three linear rows of elms. (Torkelson 2021)